How I Wrote My New Book, "Garden Disruptors,". 2

In that first rainy Covid winter, Tom and I spent days cocooned in the barn’s office. We cheated lockdown; farmworkers worked 4 hours, two days a week. But no one came inside. Polished pine, cypress, and Thai monastery colors warmed our retreat. Donkeys peered into the window, and the cat curled at the door. They warmed us too.

The new manuscript, stories of gardeners from a city just 75 miles away, sat under stacks of plant orders and other people’s finished books. Columbia, the city I’d loved over the past thirty years, and those people I written about felt very, very far away.

A silver lining shone brightly though. This winter gave time to listen to Momma’s stories, and to indulge in family stories, photos, and skeletons. I started writing. The book went sideways.

“When they tore down his house, I stacked those in the barn. He never made windows for his house, so he kept the shutters closed all the time.” Momma told me. “Why didn’t he make windows?” She sighed, “I guess he liked being drunk better than working.” There was a prevailing sadness in lots of these stories but we had the shutters.

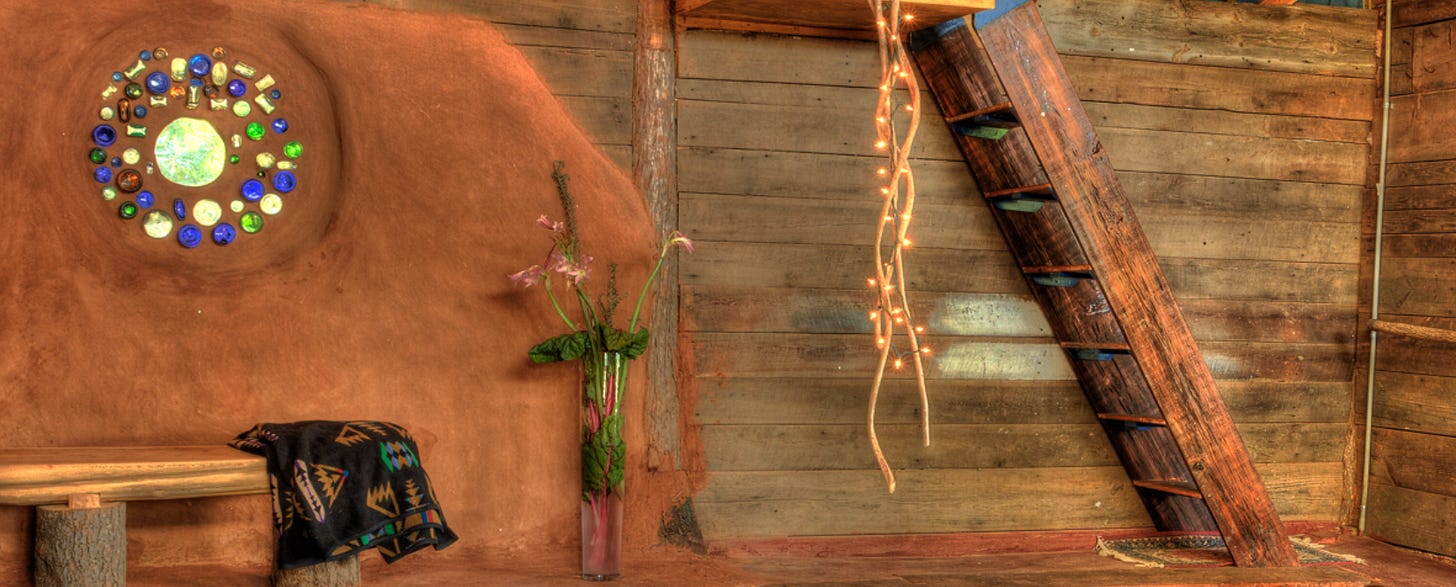

I like working, so I made a table from the shutters. The wood remains wavy, unsanded. 1930s, green paint outlawed because it contained arsenic, showing the rhythm of deep pine creases. It’s visible on one side only and only because he kept the shutters closed for 70 years. I couldn’t sand the history, the stories away. I can’t write with a pen on this table nor draw a straight line, but it’s perfect for keying into a laptop.

Tom and I hung out in the barn in the daytime, processing lily orders, reading, and playing old records. On the front porch, we set up a couch and chairs 8 feet apart, quilts, and a little heater. My sister and niece brought a swaddled bundle of blankets one afternoon—Momma’s first great-grandson. We could see only his nostrils. My sister pulled me aside; her voice shook, and she choked on tears and lament when she should have been filled with joy. The baby is ill, I thought. But no. In this world, every single interaction and every hug held anxiety. She said, “With her mask, and we’re outside, do you think it would be safe for her to hold him for a just a minute?”

Writing got personal. My garden writing needs personal layers. But I can’t write for luxury. My books have to pay the bills. The trick to a book that sells is mixing personal experience with garden lessons. Funky Little Flower Farm does that well. This new book couldn’t veer off into some sort of memoir of a crazy Southern family. I needed to keep it broadly appealing.

Lockdown helped. Old friends needed to reconnect.

Phone calls to old gardening buddies across the South veered to the past. “Remember him?”

“Do you still grow ‘Blackie’ sweet potato vine?”

“Who introduced that thing? It comes up everywhere.”

“No? I’ll send you a cutting.”

“Tony Smith died. A stroke. Does Covid cause strokes? His niece is sending his Iris to the Botanical Garden.”

Every person exclaimed, ‘It sounds like you are in an aviary!” No, I explained,

“I’m on the barn porch wrapped in a blanket. Lots of birds and animals here.” To prove it, the donkeys brayed and snorted into the speakerphone.

Before, I’d been writing about marginalized gardeners who’d found solace and community in plants. But these phone conversations changed things. The book should expand to include professional friends and explore changes in what became a pivotal time in horticulture. It could be an important history.

Until the 80s, gardening was a hobby of a few. But a flood of glossy English garden books changed that. Magazines like Southern Living began to feature hot-climate perennial gardens. Photographer, writer, and gardener Linda Askey spurred the trend in magazines and inspired millions of people, plants, and dollars in gardening businesses. She connected isolated plant lovers. She had stories.

Other professionals shared their special passions and intrigues of that special time too. These friends, slightly older, ushered in a title wave of creative gardening that made my career building public botanical gardens and now this specialty farm/nursery possible.

Even with spotty, non-broadband internet, Tom and I felt connected. But Momma and her friends, with less tech, missed clubs, church, and lunches. We realized lots of our senior customer-friends needed connections but didn’t use tech. We’d have to teach and inspire them to interact, to get online.

We started a Facebook Live show on Saturday, nothing fancy, just a walk around the farm looking at flowers and veggies and hearing the birds. It was bad reality TV. But the format allowed folks to ask questions and make comments. One day, while I droned on about turnips, someone pointed out, “Your donkeys are busy in the background. I mean BUSY. There’ll be a baby donkey on the show next year. What will we name her?” This customer, a stranger in real life, was thinking up names for our baby donkey.

A Saturday morning family formed. They shared on the show, and they emailed in stories and memories of their own. I wrote. The book spiraled out of control.

Wavy wood, old paint, and skeletons are one thing, but I like to work. I can make windows, tables, and gardens, but how could I leave, cut and focus a deluge of garden stories?

Y'all. I"m going to continue this writing about writing series through the summer. But I'm going to alternate with gardening information and other stories. So the next Substack Post will not be part of this series.

This was a bitter/ sweet post of memories of Lock Down. Well, done, Jenks.

Linda